How to Fill Out a Qualitative Research Review Form

- Review

- Open Access

- Published:

How to use and assess qualitative research methods

Neurological Research and Practice volume ii, Article number:14 (2020) Cite this article

Abstruse

This paper aims to provide an overview of the employ and assessment of qualitative research methods in the health sciences. Qualitative research can be defined as the study of the nature of phenomena and is especially appropriate for answering questions of why something is (not) observed, assessing complex multi-component interventions, and focussing on intervention comeback. The most common methods of data collection are document written report, (non-) participant observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups. For data analysis, field-notes and sound-recordings are transcribed into protocols and transcripts, and coded using qualitative data management software. Criteria such every bit checklists, reflexivity, sampling strategies, piloting, co-coding, member-checking and stakeholder involvement tin be used to enhance and assess the quality of the inquiry conducted. Using qualitative in addition to quantitative designs will equip us with improve tools to address a greater range of research problems, and to fill in bullheaded spots in current neurological enquiry and practice.

Aim

The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of qualitative research methods, including easily-on information on how they can be used, reported and assessed. This article is intended for beginning qualitative researchers in the health sciences besides as experienced quantitative researchers who wish to augment their understanding of qualitative inquiry.

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is defined as "the study of the nature of phenomena", including "their quality, dissimilar manifestations, the context in which they appear or the perspectives from which they can be perceived", but excluding "their range, frequency and place in an objectively determined chain of cause and effect" [1]. This formal definition can be complemented with a more than pragmatic rule of thumb: qualitative enquiry generally includes data in form of words rather than numbers [2].

Why conduct qualitative research?

Because some enquiry questions cannot be answered using (only) quantitative methods. For example, 1 Australian written report addressed the issue of why patients from Ancient communities often present late or not at all to specialist services offered by tertiary care hospitals. Using qualitative interviews with patients and staff, it found one of the near significant access barriers to be transportation problems, including some towns and communities merely not having a bus service to the hospital [3]. A quantitative written report could have measured the number of patients over fourth dimension or fifty-fifty looked at possible explanatory factors – but only those previously known or suspected to be of relevance. To discover reasons for observed patterns, especially the invisible or surprising ones, qualitative designs are needed.

While qualitative research is common in other fields, it is still relatively underrepresented in wellness services enquiry. The latter field is more traditionally rooted in the show-based-medicine paradigm, as seen in "inquiry that involves testing the effectiveness of various strategies to attain changes in clinical practise, preferably applying randomised controlled trial report designs (...)" [4]. This focus on quantitative research and specifically randomised controlled trials (RCT) is visible in the idea of a hierarchy of inquiry evidence which assumes that some research designs are objectively better than others, and that choosing a "lesser" design is simply acceptable when the amend ones are not practically or ethically feasible [v, 6]. Others, nevertheless, argue that an objective bureaucracy does not exist, and that, instead, the research blueprint and methods should be called to fit the specific inquiry question at mitt – "questions before methods" [2, 7,8,9]. This means that even when an RCT is possible, some research bug require a dissimilar pattern that is ameliorate suited to addressing them. Arguing in JAMA, Berwick uses the example of rapid response teams in hospitals, which he describes as "a circuitous, multicomponent intervention – essentially a process of social change" susceptible to a range of different context factors including leadership or organization history. According to him, "[in] such complex terrain, the RCT is an impoverished way to acquire. Critics who use information technology as a truth standard in this context are incorrect" [8]. Instead of limiting oneself to RCTs, Berwick recommends embracing a wider range of methods, including qualitative ones, which for "these specific applications, (...) are non compromises in learning how to ameliorate; they are superior" [8].

Inquiry bug that can exist approached particularly well using qualitative methods include assessing circuitous multi-component interventions or systems (of change), addressing questions beyond "what works", towards "what works for whom when, how and why", and focussing on intervention improvement rather than accreditation [7, nine,x,11,12]. Using qualitative methods tin as well help shed light on the "softer" side of medical handling. For example, while quantitative trials tin mensurate the costs and benefits of neuro-oncological treatment in terms of survival rates or adverse effects, qualitative enquiry tin can assist provide a amend understanding of patient or caregiver stress, visibility of affliction or out-of-pocket expenses.

How to conduct qualitative enquiry?

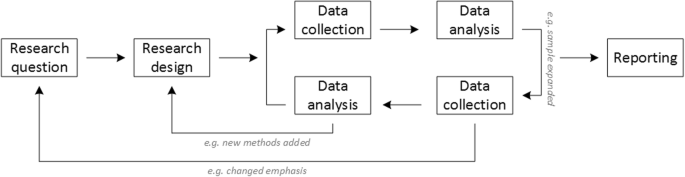

Given that qualitative enquiry is characterised by flexibility, openness and responsivity to context, the steps of data collection and analysis are not as divide and sequent as they tend to be in quantitative research [13, 14]. Every bit Fossey puts it: "sampling, information collection, analysis and interpretation are related to each other in a cyclical (iterative) manner, rather than following one subsequently another in a stepwise approach" [fifteen]. The researcher can brand educated decisions with regard to the choice of method, how they are implemented, and to which and how many units they are practical [13]. Equally shown in Fig. i, this can involve several back-and-forth steps betwixt data collection and assay where new insights and experiences can atomic number 82 to adaption and expansion of the original programme. Some insights may also necessitate a revision of the research question and/or the research design as a whole. The process ends when saturation is accomplished, i.e. when no relevant new information tin can be plant (see also below: sampling and saturation). For reasons of transparency, information technology is essential for all decisions too every bit the underlying reasoning to be well-documented.

Iterative inquiry process

While it is not always explicitly addressed, qualitative methods reverberate a different underlying inquiry paradigm than quantitative research (east.thou. constructivism or interpretivism as opposed to positivism). The choice of methods can be based on the respective underlying substantive theory or theoretical framework used by the researcher [2].

Data drove

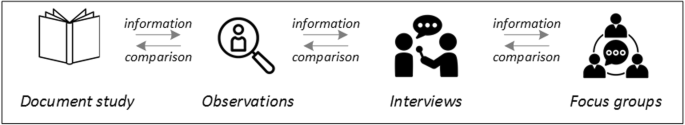

The methods of qualitative data collection most commonly used in health research are document written report, observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups [one, xiv, 16, 17].

Document report

Certificate report (also called certificate analysis) refers to the review by the researcher of written materials [14]. These can include personal and non-personal documents such as archives, almanac reports, guidelines, policy documents, diaries or letters.

Observations

Observations are especially useful to proceeds insights into a sure setting and actual behaviour – as opposed to reported behaviour or opinions [13]. Qualitative observations can be either participant or not-participant in nature. In participant observations, the observer is office of the observed setting, for instance a nurse working in an intensive intendance unit of measurement [18]. In not-participant observations, the observer is "on the outside looking in", i.due east. present in just not office of the state of affairs, trying not to influence the setting past their presence. Observations can exist planned (east.yard. for three h during the day or night shift) or ad hoc (due east.grand. as before long equally a stroke patient arrives at the emergency room). During the observation, the observer takes notes on everything or certain pre-adamant parts of what is happening effectually them, for example focusing on physician-patient interactions or communication between different professional groups. Written notes tin be taken during or after the observations, depending on feasibility (which is commonly lower during participant observations) and acceptability (e.g. when the observer is perceived to exist judging the observed). Afterward, these field notes are transcribed into observation protocols. If more than than 1 observer was involved, field notes are taken independently, but notes tin can exist consolidated into i protocol after discussions. Advantages of conducting observations include minimising the distance betwixt the researcher and the researched, the potential discovery of topics that the researcher did not realise were relevant and gaining deeper insights into the real-world dimensions of the inquiry problem at paw [18].

Semi-structured interviews

Hijmans & Kuyper draw qualitative interviews as "an exchange with an informal character, a conversation with a goal" [19]. Interviews are used to gain insights into a person'southward subjective experiences, opinions and motivations – as opposed to facts or behaviours [thirteen]. Interviews can exist distinguished by the degree to which they are structured (i.e. a questionnaire), open (eastward.g. free chat or autobiographical interviews) or semi-structured [2, 13]. Semi-structured interviews are characterized by open-ended questions and the employ of an interview guide (or topic guide/list) in which the wide areas of involvement, sometimes including sub-questions, are defined [xix]. The pre-defined topics in the interview guide tin exist derived from the literature, previous research or a preliminary method of data collection, east.g. document study or observations. The topic listing is usually adapted and improved at the start of the data collection procedure as the interviewer learns more about the field [20]. Beyond interviews the focus on the different (blocks of) questions may differ and some questions may be skipped altogether (e.one thousand. if the interviewee is not able or willing to answer the questions or for concerns almost the total length of the interview) [20]. Qualitative interviews are usually non conducted in written format every bit it impedes on the interactive component of the method [20]. In comparison to written surveys, qualitative interviews have the reward of being interactive and assuasive for unexpected topics to sally and to exist taken upward by the researcher. This tin also help overcome a provider or researcher-centred bias often found in written surveys, which by nature, can merely measure what is already known or expected to be of relevance to the researcher. Interviews can be audio- or video-taped; only sometimes it is merely feasible or adequate for the interviewer to accept written notes [xiv, 16, 20].

Focus groups

Focus groups are group interviews to explore participants' expertise and experiences, including explorations of how and why people conduct in certain ways [ane]. Focus groups normally consist of half-dozen–viii people and are led by an experienced moderator following a topic guide or "script" [21]. They can involve an observer who takes note of the non-exact aspects of the situation, possibly using an observation guide [21]. Depending on researchers' and participants' preferences, the discussions tin can be audio- or video-taped and transcribed afterwards [21]. Focus groups are useful for bringing together homogeneous (to a lesser extent heterogeneous) groups of participants with relevant expertise and experience on a given topic on which they can share detailed information [21]. Focus groups are a relatively easy, fast and cheap method to proceeds admission to data on interactions in a given group, i.e. "the sharing and comparing" amidst participants [21]. Disadvantages include less control over the process and a lesser extent to which each individual may participate. Moreover, focus group moderators need experience, equally practise those tasked with the analysis of the resulting data. Focus groups tin be less appropriate for discussing sensitive topics that participants might be reluctant to disembalm in a group setting [thirteen]. Moreover, attention must exist paid to the emergence of "groupthink" also as possible power dynamics within the group, eastward.yard. when patients are awed or intimidated by health professionals.

Choosing the "right" method

As explained above, the schoolhouse of thought underlying qualitative research assumes no objective hierarchy of evidence and methods. This ways that each selection of unmarried or combined methods has to be based on the enquiry question that needs to be answered and a critical assessment with regard to whether or to what extent the called method can accomplish this – i.east. the "fit" between question and method [14]. It is necessary for these decisions to exist documented when they are being made, and to be critically discussed when reporting methods and results.

Let us presume that our research aim is to examine the (clinical) processes effectually acute endovascular handling (EVT), from the patient's arrival at the emergency room to recanalization, with the aim to identify possible causes for filibuster and/or other causes for sub-optimal treatment outcome. As a commencement stride, we could conduct a certificate report of the relevant standard operating procedures (SOPs) for this phase of care – are they upwards-to-appointment and in line with current guidelines? Do they contain whatsoever mistakes, irregularities or uncertainties that could cause delays or other problems? Regardless of the answers to these questions, the results accept to be interpreted based on what they are: a written outline of what care processes in this infirmary should look like. If we want to know what they actually await similar in practice, we can behave observations of the processes described in the SOPs. These results can (and should) be analysed in themselves, merely also in comparing to the results of the document analysis, especially as regards relevant discrepancies. Exercise the SOPs outline specific tests for which no equipment can be observed or tasks to be performed past specialized nurses who are non present during the observation? It might likewise be possible that the written SOP is outdated, but the bodily intendance provided is in line with current best practice. In guild to notice out why these discrepancies exist, it can be useful to behave interviews. Are the physicians only non aware of the SOPs (because their existence is limited to the hospital'southward intranet) or do they actively disagree with them or does the infrastructure make information technology impossible to provide the care equally described? Some other rationale for adding interviews is that some situations (or all of their possible variations for different patient groups or the day, night or weekend shift) cannot practically or ethically be observed. In this case, it is possible to ask those involved to report on their actions – being aware that this is not the same as the bodily ascertainment. A senior doc's or hospital manager's description of certain situations might differ from a nurse'due south or junior physician'southward ane, perhaps because they intentionally misrepresent facts or maybe considering different aspects of the process are visible or of import to them. In some cases, it tin can also be relevant to consider to whom the interviewee is disclosing this information – someone they trust, someone they are otherwise non connected to, or someone they doubtable or are aware of being in a potentially "unsafe" power relationship to them. Lastly, a focus group could be conducted with representatives of the relevant professional groups to explore how and why exactly they provide care around EVT. The discussion might reveal discrepancies (between SOPs and actual care or betwixt different physicians) and motivations to the researchers as well as to the focus group members that they might not have been enlightened of themselves. For the focus grouping to deliver relevant information, attention has to be paid to its composition and carry, for instance, to make sure that all participants experience safe to disclose sensitive or potentially problematic information or that the discussion is non dominated by (senior) physicians only. The resulting combination of data collection methods is shown in Fig. two.

Possible combination of data collection methods

Attributions for icons: "Volume" past Serhii Smirnov, "Interview" by Adrien Dally, FR, "Magnifying Drinking glass" past anggun, ID, "Business concern communication" by Vectors Market; all from the Noun Project

The combination of multiple information source equally described for this example tin can be referred to as "triangulation", in which multiple measurements are carried out from dissimilar angles to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under study [22, 23].

Data analysis

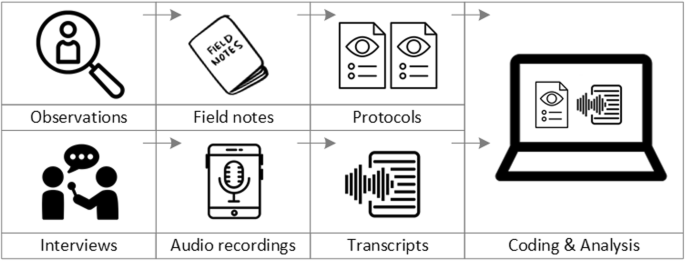

To analyse the information collected through observations, interviews and focus groups these demand to be transcribed into protocols and transcripts (see Fig. 3). Interviews and focus groups can be transcribed verbatim, with or without annotations for behaviour (east.thou. laughing, crying, pausing) and with or without phonetic transcription of dialects and filler words, depending on what is expected or known to be relevant for the analysis. In the side by side step, the protocols and transcripts are coded, that is, marked (or tagged, labelled) with one or more than brusque descriptors of the content of a judgement or paragraph [two, fifteen, 23]. Jansen describes coding equally "connecting the raw data with "theoretical" terms" [20]. In a more than practical sense, coding makes raw data sortable. This makes it possible to extract and examine all segments describing, say, a tele-neurology consultation from multiple data sources (eastward.1000. SOPs, emergency room observations, staff and patient interview). In a process of synthesis and brainchild, the codes are so grouped, summarised and/or categorised [15, twenty]. The terminate production of the coding or assay process is a descriptive theory of the behavioural pattern under investigation [twenty]. The coding process is performed using qualitative data direction software, the most mutual ones being InVivo, MaxQDA and Atlas.ti. Information technology should be noted that these are data management tools which support the analysis performed by the researcher(s) [14].

From data collection to data assay

Attributions for icons: see Fig. 2, also "Spoken language to text" past Trevor Dsouza, "Field Notes" by Mike O'Brien, U.s., "Voice Record" by ProSymbols, United states of america, "Inspection" past Fabricated, AU, and "Cloud" by Graphic Tigers; all from the Noun Project

How to report qualitative inquiry?

Protocols of qualitative research can exist published separately and in advance of the study results. However, the aim is not the same as in RCT protocols, i.east. to pre-define and set in stone the research questions and chief or secondary endpoints. Rather, it is a way to describe the research methods in detail, which might non exist possible in the results paper given journals' discussion limits. Qualitative research papers are unremarkably longer than their quantitative counterparts to allow for deep understanding and then-chosen "thick description". In the methods section, the focus is on transparency of the methods used, including why, how and past whom they were implemented in the specific report setting, so as to enable a discussion of whether and how this may have influenced data collection, assay and interpretation. The results section usually starts with a paragraph outlining the main findings, followed by more detailed descriptions of, for case, the commonalities, discrepancies or exceptions per category [20]. Here it is important to support main findings by relevant quotations, which may add information, context, emphasis or real-life examples [20, 23]. Information technology is subject area to fence in the field whether it is relevant to country the exact number or pct of respondents supporting a certain statement (e.g. "5 interviewees expressed negative feelings towards XYZ") [21].

How to combine qualitative with quantitative research?

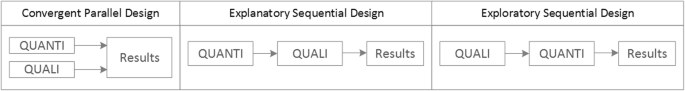

Qualitative methods tin be combined with other methods in multi- or mixed methods designs, which "[employ] two or more different methods [ …] within the same written report or research plan rather than confining the enquiry to one single method" [24]. Reasons for combining methods can be diverse, including triangulation for corroboration of findings, complementarity for illustration and clarification of results, expansion to extend the breadth and range of the study, explanation of (unexpected) results generated with 1 method with the help of another, or offsetting the weakness of one method with the strength of another [1, 17, 24,25,26]. The resulting designs can be classified co-ordinate to when, why and how the different quantitative and/or qualitative data strands are combined. The 3 most mutual types of mixed method designs are the convergent parallel design, the explanatory sequential pattern and the exploratory sequential design. The designs with examples are shown in Fig. 4.

Three common mixed methods designs

In the convergent parallel design, a qualitative study is conducted in parallel to and independently of a quantitative report, and the results of both studies are compared and combined at the phase of estimation of results. Using the in a higher place example of EVT provision, this could entail setting up a quantitative EVT registry to measure process times and patient outcomes in parallel to conducting the qualitative research outlined to a higher place, and then comparison results. Amidst other things, this would make it possible to appraise whether interview respondents' subjective impressions of patients receiving good intendance match modified Rankin Scores at follow-up, or whether observed delays in intendance provision are exceptions or the rule when compared to door-to-needle times every bit documented in the registry. In the explanatory sequential blueprint, a quantitative report is carried out commencement, followed by a qualitative study to help explain the results from the quantitative study. This would exist an appropriate design if the registry lone had revealed relevant delays in door-to-needle times and the qualitative written report would be used to empathize where and why these occurred, and how they could be improved. In the exploratory design, the qualitative study is carried out first and its results assist informing and building the quantitative study in the next step [26]. If the qualitative study effectually EVT provision had shown a loftier level of dissatisfaction among the staff members involved, a quantitative questionnaire investigating staff satisfaction could be ready in the next step, informed past the qualitative written report on which topics dissatisfaction had been expressed. Amid other things, the questionnaire design would go far possible to widen the reach of the enquiry to more respondents from unlike (types of) hospitals, regions, countries or settings, and to conduct sub-group analyses for different professional groups.

How to assess qualitative research?

A variety of assessment criteria and lists have been adult for qualitative research, ranging in their focus and comprehensiveness [xiv, 17, 27]. However, none of these has been elevated to the "gold standard" in the field. In the following, nosotros therefore focus on a set of commonly used assessment criteria that, from a practical standpoint, a researcher can await for when assessing a qualitative inquiry report or newspaper.

Checklists

Assessors should check the authors' use of and adherence to the relevant reporting checklists (e.yard. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR)) to make sure all items that are relevant for this type of research are addressed [23, 28]. Discussions of quantitative measures in add-on to or instead of these qualitative measures can exist a sign of lower quality of the enquiry (paper). Providing and adhering to a checklist for qualitative research contributes to an important quality benchmark for qualitative research, namely transparency [fifteen, 17, 23].

Reflexivity

While methodological transparency and complete reporting is relevant for all types of research, some boosted criteria must exist taken into account for qualitative research. This includes what is called reflexivity, i.e. sensitivity to the human relationship betwixt the researcher and the researched, including how contact was established and maintained, or the background and experience of the researcher(s) involved in data collection and analysis. Depending on the research question and population to exist researched this tin can be express to professional experience, but it may as well include gender, historic period or ethnicity [17, 27]. These details are relevant because in qualitative inquiry, as opposed to quantitative enquiry, the researcher every bit a person cannot be isolated from the research process [23]. Information technology may influence the conversation when an interviewed patient speaks to an interviewer who is a physician, or when an interviewee is asked to talk over a gynaecological procedure with a male interviewer, and therefore the reader must be made enlightened of these details [19].

Sampling and saturation

The aim of qualitative sampling is for all variants of the objects of observation that are deemed relevant for the study to exist present in the sample "to encounter the consequence and its meanings from as many angles as possible" [one, 16, 19, 20, 27], and to ensure "information-richness [xv]. An iterative sampling arroyo is brash, in which information drove (eastward.g. five interviews) is followed past data analysis, followed by more information drove to observe variants that are lacking in the electric current sample. This procedure continues until no new (relevant) information can exist found and farther sampling becomes redundant – which is chosen saturation [one, 15]. In other words: qualitative data collection finds its stop point non a priori, only when the research team determines that saturation has been reached [29, xxx].

This is also the reason why most qualitative studies use deliberate instead of random sampling strategies. This is generally referred to every bit "purposive sampling", in which researchers pre-define which types of participants or cases they need to include so as to comprehend all variations that are expected to exist of relevance, based on the literature, previous experience or theory (i.due east. theoretical sampling) [xiv, twenty]. Other types of purposive sampling include (only are not limited to) maximum variation sampling, critical case sampling or extreme or deviant case sampling [ii]. In the above EVT example, a purposive sample could include all relevant professional person groups and/or all relevant stakeholders (patients, relatives) and/or all relevant times of observation (day, night and weekend shift).

Assessors of qualitative research should cheque whether the considerations underlying the sampling strategy were sound and whether or how researchers tried to adjust and meliorate their strategies in stepwise or cyclical approaches between data collection and analysis to achieve saturation [fourteen].

Piloting

Good qualitative inquiry is iterative in nature, i.east. information technology goes back and forth between information collection and assay, revising and improving the approach where necessary. One case of this are pilot interviews, where dissimilar aspects of the interview (especially the interview guide, but as well, for example, the site of the interview or whether the interview tin can be audio-recorded) are tested with a small number of respondents, evaluated and revised [xix]. In doing so, the interviewer learns which wording or types of questions piece of work best, or which is the all-time length of an interview with patients who accept problem concentrating for an extended time. Of course, the same reasoning applies to observations or focus groups which tin can too exist piloted.

Co-coding

Ideally, coding should be performed by at to the lowest degree two researchers, especially at the offset of the coding process when a common approach must be divers, including the establishment of a useful coding list (or tree), and when a mutual meaning of individual codes must exist established [23]. An initial sub-set or all transcripts tin exist coded independently by the coders and and then compared and consolidated subsequently regular discussions in the research squad. This is to make sure that codes are applied consistently to the research data.

Member checking

Member checking, also called respondent validation, refers to the practice of checking back with report respondents to see if the research is in line with their views [14, 27]. This can happen after data collection or assay or when showtime results are available [23]. For instance, interviewees can be provided with (summaries of) their transcripts and asked whether they believe this to be a complete representation of their views or whether they would like to analyze or elaborate on their responses [17]. Respondents' feedback on these issues and then becomes part of the data collection and analysis [27].

Stakeholder involvement

In those niches where qualitative approaches have been able to evolve and grow, a new trend has seen the inclusion of patients and their representatives not only every bit study participants (i.east. "members", run into above) simply as consultants to and agile participants in the broader research process [31,32,33]. The underlying assumption is that patients and other stakeholders agree unique perspectives and experiences that add together value beyond their own single story, making the enquiry more relevant and beneficial to researchers, study participants and (future) patients akin [34, 35]. Using the instance of patients on or nearing dialysis, a contempo scoping review found that 80% of clinical research did not address the top 10 research priorities identified by patients and caregivers [32, 36]. In this sense, the interest of the relevant stakeholders, especially patients and relatives, is increasingly existence seen as a quality indicator in and of itself.

How not to appraise qualitative inquiry

The in a higher place overview does non include certain items that are routine in assessments of quantitative research. What follows is a not-exhaustive, non-representative, experience-based listing of the quantitative criteria frequently applied to the cess of qualitative enquiry, every bit well as an caption of the limited usefulness of these endeavours.

Protocol adherence

Given the openness and flexibility of qualitative research, information technology should not be assessed past how well it adheres to pre-adamant and fixed strategies – in other words: its rigidity. Instead, the assessor should look for signs of adaptation and refinement based on lessons learned from earlier steps in the research process.

Sample size

For the reasons explained above, qualitative enquiry does not require specific sample sizes, nor does it require that the sample size be adamant a priori [1, 14, 27, 37,38,39]. Sample size can only be a useful quality indicator when related to the research purpose, the called methodology and the limerick of the sample, i.e. who was included and why.

Randomisation

While some authors fence that randomisation tin can exist used in qualitative research, this is non unremarkably the case, as neither its feasibility nor its necessity or usefulness has been assuredly established for qualitative research [thirteen, 27]. Relevant disadvantages include the negative bear on of a besides large sample size equally well as the possibility (or probability) of selecting "tranquillity, uncooperative or inarticulate individuals" [17]. Qualitative studies practice not utilise control groups, either.

Interrater reliability, variability and other "objectivity checks"

The concept of "interrater reliability" is sometimes used in qualitative enquiry to assess to which extent the coding approach overlaps betwixt the 2 co-coders. However, it is not clear what this measure tells us about the quality of the analysis [23]. This means that these scores can exist included in qualitative research reports, preferably with some additional information on what the score means for the analysis, merely information technology is not a requirement. Relatedly, information technology is not relevant for the quality or "objectivity" of qualitative research to separate those who recruited the study participants and collected and analysed the information. Experiences fifty-fifty show that information technology might be ameliorate to have the same person or team perform all of these tasks [20]. First, when researchers introduce themselves during recruitment this can heighten trust when the interview takes place days or weeks subsequently with the same researcher. 2nd, when the sound-recording is transcribed for analysis, the researcher conducting the interviews will usually remember the interviewee and the specific interview situation during data assay. This might be helpful in providing additional context information for interpretation of data, e.g. on whether something might have been meant as a joke [18].

Not existence quantitative research

Being qualitative research instead of quantitative research should not exist used every bit an cess benchmark if it is used irrespectively of the research problem at mitt. Similarly, qualitative research should not be required to be combined with quantitative research per se – unless mixed methods research is judged as inherently better than single-method research. In this example, the same criterion should be practical for quantitative studies without a qualitative component.

Conclusion

The main take-away points of this newspaper are summarised in Table 1. We aimed to show that, if conducted well, qualitative inquiry can answer specific inquiry questions that cannot to be adequately answered using (only) quantitative designs. Seeing qualitative and quantitative methods as equal volition help united states of america become more enlightened and disquisitional of the "fit" between the enquiry problem and our chosen methods: I can conduct an RCT to decide the reasons for transportation delays of acute stroke patients – but should I? It also provides us with a greater range of tools to tackle a greater range of research problems more appropriately and successfully, filling in the blind spots on i half of the methodological spectrum to better address the whole complexity of neurological inquiry and exercise.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- EVT:

-

Endovascular treatment

- RCT:

-

Randomised Controlled Trial

- SOP:

-

Standard Operating Procedure

- SRQR:

-

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Inquiry

References

-

Philipsen, H., & Vernooij-Dassen, M. (2007). Kwalitatief onderzoek: nuttig, onmisbaar en uitdagend. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk. [Qualitative research: useful, indispensable and challenging. In: Qualitative research: Practical methods for medical practice (pp. 5–12). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

-

Punch, K. F. (2013). Introduction to social research: Quantitative and qualitative approaches. London: Sage.

-

Kelly, J., Dwyer, J., Willis, E., & Pekarsky, B. (2014). Travelling to the city for hospital care: Access factors in country aboriginal patient journeys. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 22(3), 109–113.

-

Nilsen, P., Ståhl, C., Roback, Thou., & Cairney, P. (2013). Never the twain shall meet? - a comparison of implementation science and policy implementation enquiry. Implementation Science, 8(1), 1–12.

-

Howick J, Chalmers I, Glasziou, P., Greenhalgh, T., Heneghan, C., Liberati, A., Moschetti, I., Phillips, B., & Thornton, H. (2011). The 2011 Oxford CEBM testify levels of evidence (introductory document). Oxford Center for Evidence Based Medicine. https://www.cebm.cyberspace/2011/06/2011-oxford-cebm-levels-bear witness-introductory-certificate/.

-

Eakin, J. Chiliad. (2016). Educating critical qualitative health researchers in the land of the randomized controlled trial. Qualitative Enquiry, 22(2), 107–118.

-

May, A., & Mathijssen, J. (2015). Alternatieven voor RCT bij de evaluatie van effectiviteit van interventies!? Eindrapportage. In Alternatives for RCTs in the evaluation of effectiveness of interventions!? Final report.

-

Berwick, D. M. (2008). The scientific discipline of improvement. Periodical of the American Medical Clan, 299(ten), 1182–1184.

-

Christ, T. W. (2014). Scientific-based research and randomized controlled trials, the "gold" standard? Alternative paradigms and mixed methodologies. Qualitative Enquiry, 20(1), 72–80.

-

Lamont, T., Barber, N., Jd, P., Fulop, North., Garfield-Birkbeck, S., Lilford, R., Mear, L., Raine, R., & Fitzpatrick, R. (2016). New approaches to evaluating complex wellness and care systems. BMJ, 352:i154.

-

Drabble, S. J., & O'Cathain, A. (2015). Moving from Randomized Controlled Trials to Mixed Methods Intervention Evaluation. In South. Hesse-Biber & R. B. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Multimethod and Mixed Methods Research Research (pp. 406–425). London: Oxford University Press.

-

Chambers, D. A., Glasgow, R. E., & Stange, K. C. (2013). The dynamic sustainability framework: Addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing modify. Implementation Science : IS, eight, 117.

-

Hak, T. (2007). Waarnemingsmethoden in kwalitatief onderzoek. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk. [Observation methods in qualitative enquiry] (pp. xiii–25). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

-

Russell, C. M., & Gregory, D. M. (2003). Evaluation of qualitative research studies. Prove Based Nursing, vi(2), 36–40.

-

Fossey, E., Harvey, C., McDermott, F., & Davidson, Fifty. (2002). Agreement and evaluating qualitative research. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36, 717–732.

-

Yanow, D. (2000). Conducting interpretive policy analysis (Vol. 47). Thou Oaks: Sage Academy Papers Series on Qualitative Research Methods.

-

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Teaching for Information, 22, 63–75.

-

van der Geest, S. (2006). Participeren in ziekte en zorg: meer over kwalitatief onderzoek. Huisarts en Wetenschap, 49(4), 283–287.

-

Hijmans, E., & Kuyper, One thousand. (2007). Het halfopen interview als onderzoeksmethode. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk. [The half-open up interview as research method (pp. 43–51). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

-

Jansen, H. (2007). Systematiek en toepassing van de kwalitatieve survey. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk. [Systematics and implementation of the qualitative survey (pp. 27–41). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

-

Pv, R., & Peremans, 50. (2007). Exploreren met focusgroepgesprekken: de 'stem' van de groep onder de loep. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk. [Exploring with focus group conversations: the "voice" of the group under the magnifying glass (pp. 53–64). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

-

Carter, N., Bryant-Lukosius, D., DiCenso, A., Blythe, J., & Neville, A. J. (2014). The utilise of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41(5), 545–547.

-

Boeije H: Analyseren in kwalitatief onderzoek: Denken en doen, [Analysis in qualitative research: Thinking and doing] vol. Den Haag Boom Lemma uitgevers; 2012.

-

Hunter, A., & Brewer, J. (2015). Designing Multimethod Research. In S. Hesse-Biber & R. B. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Multimethod and Mixed Methods Research Inquiry (pp. 185–205). London: Oxford University Press.

-

Archibald, M. Thou., Radil, A. I., Zhang, 10., & Hanson, W. E. (2015). Current mixed methods practices in qualitative research: A content analysis of leading journals. International Periodical of Qualitative Methods, fourteen(2), five–33.

-

Creswell, J. Westward., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Choosing a Mixed Methods Design. In Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

-

Mays, Northward., & Pope, C. (2000). Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ, 320(7226), 50–52.

-

O'Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine : Journal of the Clan of American Medical Colleges, 89(nine), 1245–1251.

-

Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Bakery, South., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative enquiry: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality and Quantity, 52(4), 1893–1907.

-

Moser, A., & Korstjens, I. (2018). Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Office 3: Sampling, information collection and analysis. European Journal of General Practice, 24(one), 9–18.

-

Marlett, N., Shklarov, S., Marshall, D., Santana, M. J., & Wasylak, T. (2015). Building new roles and relationships in enquiry: A model of patient engagement research. Quality of Life Research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation, 24(5), 1057–1067.

-

Demian, K. Northward., Lam, Northward. N., Mac-Way, F., Sapir-Pichhadze, R., & Fernandez, N. (2017). Opportunities for engaging patients in kidney inquiry. Canadian Periodical of Kidney Health and Illness, 4, 2054358117703070–2054358117703070.

-

Noyes, J., McLaughlin, L., Morgan, M., Roberts, A., Stephens, Grand., Bourne, J., Houlston, M., Houlston, J., Thomas, S., Rhys, R. Thou., et al. (2019). Designing a co-productive study to overcome known methodological challenges in organ donation enquiry with bereaved family members. Health Expectations. 22(4):824–35.

-

Piil, K., Jarden, 1000., & Pii, G. H. (2019). Research calendar for life-threatening cancer. European Periodical Cancer Care (Engl), 28(1), e12935.

-

Hofmann, D., Ibrahim, F., Rose, D., Scott, D. L., Cope, A., Wykes, T., & Lempp, H. (2015). Expectations of new treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: Developing a patient-generated questionnaire. Health Expectations : an international journal of public participation in health care and wellness policy, 18(5), 995–1008.

-

Jun, Thousand., Manns, B., Laupacis, A., Manns, L., Rehal, B., Crowe, S., & Hemmelgarn, B. R. (2015). Assessing the extent to which current clinical research is consistent with patient priorities: A scoping review using a case study in patients on or nearing dialysis. Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease, two, 35.

-

Elsie Bakery, S., & Edwards, R. (2012). How many qualitative interviews is enough? In National Heart for Enquiry Methods Review Paper. National Heart for Inquiry Methods. http://eprints.ncrm.air conditioning.u.k./2273/four/how_many_interviews.pdf.

-

Sandelowski, M. (1995). Sample size in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health, 18(2), 179–183.

-

Sim, J., Saunders, B., Waterfield, J., & Kingstone, T. (2018). Tin sample size in qualitative research be determined a priori? International Periodical of Social Research Methodology, 21(v), 619–634.

Funding

no external funding.

Writer information

Affiliations

Contributions

LB drafted the manuscript; WW and CG revised the manuscript; all authors canonical the terminal versions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This commodity is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits utilise, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, every bit long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Eatables licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the commodity's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the commodity's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is non permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

Nearly this article

Cite this article

Busetto, L., Wick, W. & Gumbinger, C. How to use and appraise qualitative inquiry methods. Neurol. Res. Pract. ii, 14 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42466-020-00059-z

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1186/s42466-020-00059-z

Keywords

- Qualitative research

- Mixed methods

- Quality assessment

Source: https://neurolrespract.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s42466-020-00059-z

0 Response to "How to Fill Out a Qualitative Research Review Form"

Post a Comment